How is coffee decaffeinated?

Dive into the fascinating world of decaffeinated coffee!

From its early artisanal techniques to safer modern methods, discover how caffeine is extracted, what concerns exist regarding its potential toxicity and environmental impact. Whether you’re a decaf enthusiast or simply curious, this article offers you a complete overview to inform your consumption choices.

I’ve often wondered: how is coffee decaffeinated?

After my research, other questions emerged: is decaffeinated coffee toxic? What is the environmental impact of the processes? If, like me, you enjoy savoring a decaf from time to time, you’ll want to know what goes on behind the scenes of its production.

A study revealed that even when decaffeinated, some beverages retain 1 to 2% (and sometimes up to 20%) of their initial caffeine content.

A bit of history

In 1820, chemist Friedlieb Ferdinand Runge succeeded in isolating pure caffeine. He didn’t seek to patent his process for decaffeinated coffee: his goal was primarily scientific.

The first commercial process was invented by German Ludwig Roselius in 1903 (patented in 1906), discovered by chance when his cargo of beans soaked in seawater during transport. Result: a large portion of the caffeine had disappeared, but not the taste.

The first industrial processes used steam, acids, bases and… benzene! The latter being carcinogenic, it was abandoned. Since then, methods have evolved toward less toxic alternatives.

The common principles of decaffeination

Decaffeination is always done on green beans (unroasted).

The challenge: remove only the caffeine while preserving the other compounds responsible for taste and aroma.

Since caffeine is water-soluble and polar, water is used in all processes. But because it is not selective, a decaffeinating agent is often used: methylene chloride, activated carbon, CO₂, or ethyl acetate.

The main decaffeination methods

1. By organic solvents

Today, the following are mainly used:

- Dichloromethane: effective but slightly toxic, it must be present at less than 10 ppm in the finished product.

- Ethyl acetate: also slightly toxic, but presented as “natural” when derived from sugar cane fermentation.

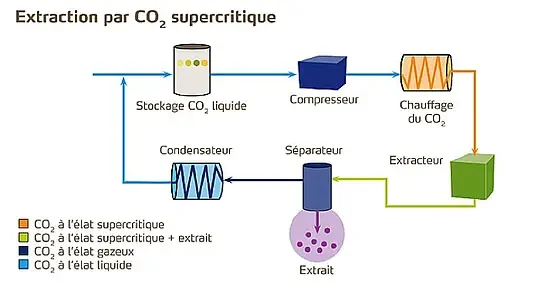

2. Supercritical CO₂ extraction

Here, CO₂ in a supercritical state acts as a solvent to selectively extract caffeine, without altering the aromas.

This process avoids the use of potentially harmful chemicals and produces decaffeinated coffee of commercial quality.

3. Water decaffeination

The beans are soaked in hot water saturated with aromatic components to limit their loss.

The water then passes through an activated carbon filter that retains the caffeine, before being reintroduced into the beans. Result: a coffee with good aroma, without chemical solvents.